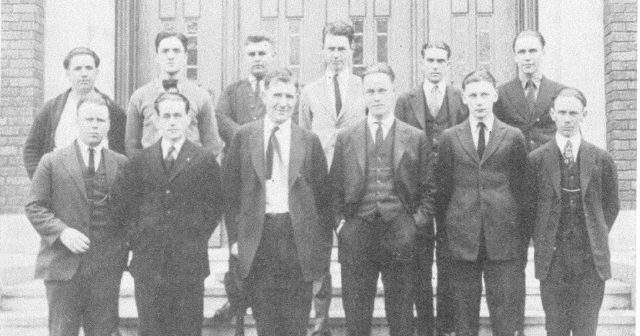

The First Mustard Seed Group, from the Blue Jay Yearbook 1921

In the early years of Westminster, campus activities had no person in charge, organized plan, or source of financing. Various students who were interested in a certain activity or cause would pick up the responsibilities for that particular area, come up with finances, and keep it going.

Realizing how inefficient this practice was, a group of concerned students met in Swope Chapel on a Monday afternoon in March of 1921 to form a new organization to finance and promote activities on campus.

The Mustard Seed organization was formed that day, with English and Political Science Professor Franc Lewis McCluer as the sponsor.

One early yearbook editor pointed out that the word “mustard” made him ill because he had childhood memories of swallowing half a bottle of strong mustard, but the origin of the group’s name actually came from a much happier connotation.

The name was chosen because of the parable of the mustard seed, for even though the mustard was the smallest of all seeds, great things could result from its planting.

As the organization’s motto stated: “The smallest of seeds, and yet it grows so large that birds may roost in its branches.”

With the leader of its group officially known as the “Kernel,” The Mustard Seed went to work “putting into campus life some of the pep of that condiment whose name they bear,” one yearbook stated.

Over the next few years, the club became one of the most active and dependable organizations at Westminster, and membership was coveted because the group was so exclusive.

Only twelve men could be members of The Mustard Seed. These members were chosen at the first of each academic year by the remaining members of the previous year’s organization. So the number chosen each year was equal to the number of members the organization had lost to graduation.

The new members were chosen in October, and they could be recognized on campus because of the long rope girdle around the waist they were required to wear as the pledging insignia of the organization. The excess rope hung from their spinal column and often looked like a tail, and after they wore it for a while, the tail would become frayed.

One student observed: “It is the height of sport to touch a match to the tail and watch the startled person travel. Another quaint whimsy is to wrap the tail around the subject’s neck and gently choke him to death. In recent years, however, the faculty has ceased to sanction this sort of treatment.”

The Mustard Seed’s time of activity was short; usually going strong during football season and then “hibernating” for winter.

Members of The Mustard Seed were known as “men who have the old Westminster spirit at heart and are willing to do everything in their power to make this the best school in the West.” The 1930 yearbook says: “Their coffee may be cold but their enthusiasm is not. Their philosophy in life is ‘a bug in your coffee is worth two with no coffee at all.'”

The Mustard Seed made most of its money from selling concessions at football games where, according to sources on hand, they “dispensed succulent dogs, the weak but hot coffee, and other dainties to the multitude desiring their bread and circuses at the same time.” The group sold everything from hot dogs and candy to chewing gum and cigarettes.

Among the group’s responsibilities were selling tickets at events, chartering trains and buses to important games, managing the plays, and holding campus fairs.

The money raised by the group was turned over to different organizations at the College. The comedy-drama “All-of-a-Sudden Peggy” was presented in 1921 with contributions going to the athletic teams. New baseball uniforms were purchased that year.

In 1922-23, money was divided between the debating team and the Athletic Association.

In the fall of 1923, a contribution of $75 was made for the purchase of Blue Jay athletic shirts.

The money was used to present gold footballs to the football team in 1924.

At the end of the semester, all remaining funds were turned over to the Athletic Association, which always ran at a deficit.

By 1930 The Mustard Seeds still had the requisite 12 members and were said to be “far from beautiful” but so artful “they could put on a successful campaign selling children’s shaving mugs.”

In 1931 the group had dropped to nine members; by 1932 only eight.

After that, no mention can be found of the group, so Westeryears assumes the organization had outlasted its usefulness, and the College had found other means to finance campus activities.

Its existence was short but glorious. The Mustard Seed was obviously a very coveted honor and memorable in its heyday.

One of the last yearbook entries about The Mustard Seed gives a great account of their activities:

“And so it is, gentle reader, when you have been to a football game, you, no doubt, met a youth with a box of sundries (cold hot-dogs to cigarets) who accosted you thus:

‘Hey, hey, how about your hot dog, cigarets, chewing gum, or candy?

Has the little lady had her Milky Way or Hershey?’

He will accent every other syllable and do his best to make you feel that your nickel will pull the college out of debt.

If you have had the misfortune to bring a Willie or a date of other doubtful nationality, she will place her hand on your arm and look so appealingly into your eyes with her ‘big, blue, limpid pools’ of eyes that you will either yield or feel that you have become a most debased menial.

Yes, it is his duty to filch you of your share of the coin of the realm.

And should you have a nickel in your pocket when the game is over, if the little Mustard Seed knows about it, his whole day will be ruined.

Personally, I have never brought more than four cents to a game in three years—that gripes them.”

This is the editorial account for Westminster College news team. Please feel free to get in touch if you have any questions or comments.