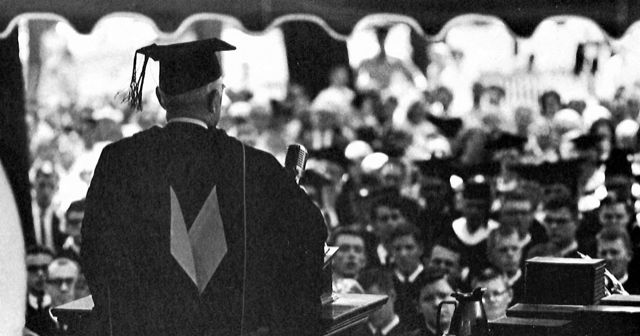

As the 107 graduates gathered on June 8, 1964, for the outdoor commencement exercises—the largest Westminster graduating class in the school’s history at that time—they had no idea that, rather than the customary sage advice and motivational urgings delivered by most orators on this occasion, their famous commencement speaker for the day would give them a lesson in history.

Yet had they known the “Man from Missouri,” former U.S. President Harry S. Truman well, they would have hardly been surprised.

Plagued by poor eyesight from boyhood, young Truman found great joy in reading, particularly about history. In his insightful article for the National Archives, “Harry Truman’s History Lessons,” Samuel W. Rushay, Jr., the supervisory archivist at the Truman Library and Museum, recalls Truman saying that at the age of ten, his mother had presented him with “a blackboard on the back of which was a column of about four or five paragraphs on every President up to that time, which included Grover Cleveland, and that’s where I got interested in the history of the country.” So Truman’s commencement address at Westminster, which focused on the office of the presidency, had early roots.

Plagued by poor eyesight from boyhood, young Truman found great joy in reading, particularly about history. In his insightful article for the National Archives, “Harry Truman’s History Lessons,” Samuel W. Rushay, Jr., the supervisory archivist at the Truman Library and Museum, recalls Truman saying that at the age of ten, his mother had presented him with “a blackboard on the back of which was a column of about four or five paragraphs on every President up to that time, which included Grover Cleveland, and that’s where I got interested in the history of the country.” So Truman’s commencement address at Westminster, which focused on the office of the presidency, had early roots.

Truman was certainly no stranger to Westminster and a great friend to the institution. His personal note at the bottom of the invitation to Sir Winston Churchill, orchestrated by his military aide, Major General Harry Vaughan, a 1916 graduate from Westminster, was a major factor in the former Prime Minister of Great Britain coming to Westminster to deliver one of the most significant addresses in history on its campus: the famous “Iron Curtain” speech in 1946. President Truman’s pledge to introduce “The Last Lion” was the piece de resistance in bringing Churchill to this small liberal arts college in America’s Heartland. Truman also had delivered the Green Lecture himself in 1954 and received an honorary degree from Westminster.

Only two months before commencement, on April 19, Truman had attended the official groundbreaking ceremony for the National Churchill Memorial. College historian and former Westminster history professor Dr. Bill Parrish recalls that following his own remarks framing the historical perspective of the day, once he had returned to his seat, President Truman left his own seat on the front row to follow Parrish in order to say to him: “Young man, that’s a great speech. That’s just the way it was.”

Truman always looked to the lessons of history and the decisions of the great leaders throughout the ages to guide him in making presidential decisions. As the Man from Independence was fond of saying, “there is nothing new in the world except the history you do not know.”

Earlier in the week Truman had canceled other plans because of a stomach disorder, but he refused to miss the 10:30 a.m. commencement address that Monday morning.

At 9:00 a.m. Major General Vaughan had commissioned the ROTC members of the graduating class.

Baccalaureate services had been held the day before at the First Presbyterian Church with the Rev. James L. Cottrell of Omaha, NE delivering the sermon.

As was the custom at that time, graduates made their traditional march through The Columns to open the commencement exercises.

Honorary degrees of law were presented that day to Charles Patrick Clark, Washington D.C. lawyer, lobbyist, and former Truman staff member; Edwin M. Clark, President of Southwestern Bell Company in St. Louis; and Carl Trauernicht, Sr, St. Louis lawyer and retiring Chairman of the Westminster Board of Trustees.

President Truman began his commencement remarks by speaking about the importance of officially preserving “the utterances and acts of the Presidency.”

“Future generations are entitled to know what Presidents said in their other public appearances,” said Truman. “By studying all of their speeches, scholars can get a better idea of what the fellow was really like and how he arrived at the decisions.”

In his Green Lecture, Truman had lectured about the importance of the preservation of Presidential papers and said the burning of the important papers such as those of Lincoln and Fillmore by “their misguided sons” should never happen again.

In his commencement remarks, Truman praised President Franklin Roosevelt for setting the precedent of preserving all his presidential papers as “the property of the nation,” and told students how he had turned all his papers over to the Truman Presidential Library in Independence for research and study. “On dedication day, July 6, 1957, the building and all its contents were turned over to the Federal Government for operation by the National Archives.”

Thanks to Truman and Roosevelt’s example, the Presidential Records Act was finally approved in 1978 making the legal ownership of the President and Vice President’s official records public property rather than private and mandating the preservation of all records.

Truman’s commencement remarks outlined six jobs of the President:

“To take care that laws are faithfully executed”;

“Be commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces”;

Serve as “the foreign policymaker of the nation”;

“Give Congress information on the state of the union and recommend measures for their consideration”;

Act as “the head of his political party (“convince the people that his party can run the national government better than the opposition,” but at the same time “never forget that he is responsible to all the people of the nation” and their welfare)”; and

Be “the social host of the nation.”

On the last point, Truman’s famous personal candor blossomed fully as he told the graduates: “A great many of the stuffed-shirt people like this very much…” and …”if you think it is a lot of fun to shake hands with 2,700 people [at a state dinner], whose names you can’t understand even when they are pronounced, I wish you could try it sometime.” The former president estimated to the crowd that in his last year in the White House, Mrs. Truman shook hands with almost 50,000 people, and he “shook hands with 25,000 and dodged the rest.”

Another of Truman’s candid opinion came through in a couple of subtle references: his known disdain for the current President Dwight Eisenhower. Eisenhower had been highly critical of Truman’s actions as president and had refused his invitation to have coffee at the White House before the inaugural ceremony. Truman never called Eisenhower by name in his speech, but referred to him instead as the “current occupant” and said, “I may not agree with him politically, and I reserve the right to say whether he is doing his work well or badly, but he still has my sympathy, because I know exactly what he is up against.”

The rest of Truman’s commencement speech gave a very brief description of the accomplishments or failures of each President from Washington to Roosevelt postulating the theory that strong Presidential leaders are usually followed by weaker ones. In his typical modest manner about his own abilities and accomplishments, he referred to Roosevelt as “another of the greatest of the great Presidents who came along and saved the Republic.”

He concluded his remarks by urging the graduates to “become more curious about the history of your country and the world and follow through, by hard work, to keep this republic the greatest in the history of the world.”

His final optimistic thought to the class was: “When the country needs leadership, it always comes forward.”

President Truman was honored again that day when Westminster President Robert L.D.Davidson announced the President would be the first occupant of the newly-established Truman Chair of History at Westminster and return to deliver several lectures during the following school year. The month before commencement at President Truman’s 80th birthday celebration in Washington, D.C., Charles Patrick Clark, Associate Chief Counsel for the Truman Committee when Truman was a U.S. Senator in 1943, and then a lawyer and lobbyist, had announced that after a year of fundraising, $80,000 had been raised for the Westminster History Chair. President Lyndon Johnson was a surprise visitor at that dinner. Johnson told the crowd of Truman: “No man in American political life has won more respect. For one thing, his actions as President still form the bedrock of our foreign policy.”

Unfortunately, President Truman was unable to fulfill any of the grand plans made that commencement day for future Westminster appearances. In fact, his commencement speech at Westminster, which was the only commencement speech he delivered in 1964, was one of his last public appearances.

Dr. Bill Parrish recalls that he and Westminster President Davidson drove to the Truman Library to meet with the President after his commencement address. Truman took them on a personal tour of the Library as he loved to do, and Parrish remembers vividly ending up in the Reading Room in front of a portrait of Truman in full regalia as Grand Marshal of the Masonic Lodge. Truman informed the two that his health would not allow him to travel to Westminster, but if the College wanted to bring groups of students to the Truman Library, he would speak to them in the lecture hall there.

After the two men left that day, they were told that Truman had fallen in his home, which prompted a decline in health from which Truman never recovered.

President Truman died December 26, 1972, and although he was never able to meet with Westminster students again, the staff at the Truman Library for a number of years would graciously host at least two or three Westminster students to do summer research on their senior thesis there and even furnished them with lodging on weekends.

President Truman’s last words to the class of 1964 were certainly true, for when America needed leadership most following World War II and the sudden death of Roosevelt, the Man from Independence stepped to the forefront to become one of our country’s greatest Presidents.

This is the editorial account for Westminster College news team. Please feel free to get in touch if you have any questions or comments.

You must be logged in to post a comment.