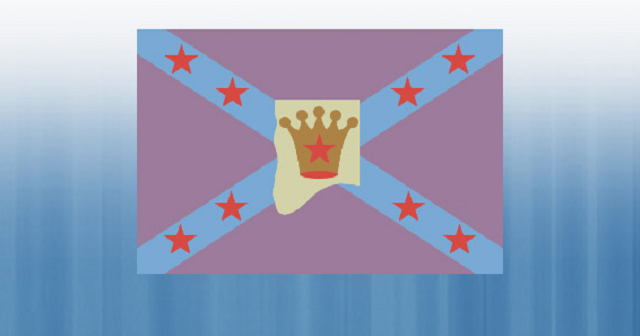

Featured is the official flag of the Kingdom of Callaway.

In 1961, the 100th anniversary of the Kingdom’s foundation, the Callaway County Court signed a court order establishing the official flag of the Kingdom. The order is as follows:

“Be it resolved by the County Court of Callaway County, Missouri that a flag having a royal purple background, emblematic of the royalty of the county; bearing two blue bars representing the battles of Moore’s Mill and Overton’s Run; having its center on a white background an outline of this county over which there is a golden crown; indicating that this is a kingdom; over which there are five jewels representing the five major rivers in the county, Missouri, Auxvasse, Middle, Cedar and Town Creek; the crown having a red lining representing the precious blood shed by the citizens of this county in the War Between the States; the bars heretofore noted bearing eight stars representing the townships in 1891, they being Bourbon, Cedar, Cote Sans, Dessein, Liberty, Nine Mile Prairie, Round Prairie, and St. Aubert; and the center star representing Fulton; be and is hereby adopted as the official flag of Callaway County, Missouri; that upon all public occasions it shall be displayed; that the Kingdom of Callaway Historical Society be and is thereby made the official custodian of this flag which was today viewed by us, and that we hereby grant to aforesaid society the exclusive privilege to make and disseminate all representations of this flag.

Done by order of the Callaway County Court.”

Callaway County during the Civil War was certainly a hotbed of turmoil. While Callaway County was predominantly in lockstep with Missouri’s pro-Southern Governor Claiborne Jackson, the strong Union forces of General Nathaniel Lyon kept Missouri from following Governor Jackson’s call for the state to secede from the Union and ultimately forced Governor Jackson to flee the state. In spite of the Kingdom of Callaway’s Southern sympathies, a strong Federal presence at the Fulton Hospital for the Insane, which was used as both as a barracks and a prison by the Union troops, kept the situation under control.

Miraculously, in the midst of all this, Westminster College remained the only college outside of St. Louis that did not close during the Civil War, even though the fall 1861 term had to be delayed until December because four of the five faculty members had resigned and time was needed to replace them. Yet the student population thrived, reaching almost two hundred, the largest number in the school’s short history. Most authorities believe a law that forbade drafting students into the army played a significant role in those larger enrollments.

Yet in spite of the sea of conflict surrounding the College, Westminster remained an island of calm. Student sympathy was primarily with the Confederates and several had enlisted in the Callaway Guards. However, the faculty forbade the discussion of political questions in the school literary societies and strictly kept personal encounters among students over the war from occurring.

With lively discussions and passionate opinions suppressed and intercollegiate athletic activities unheard of at this time, the men of Westminster College often found another outlet for their energy—pranks. While one historian referred to the student body of the time as “a bit lively,” a Fulton local said: “the meanest lot of boys that ever lived went to college in Fulton between 1860 and 1865.”

One anecdote from the time concerned Dr. J.H. Scott, the mathematics professor, who as student-tutor had the duty of calling roll at chapel exercises. His desk was on the platform, and he kept the roll of student names inside it. On one particular morning, he came in a few minutes early and before he could unlock his desk heard a noise coming from inside. Realizing he was about to become the victim of a practical joke, he changed course and went to his classroom, returning with a duplicate roll to use that morning. At noon, when every boy had left the building, he opened the desk and out flew an old setting hen, enraged by her captivity.

Taking the rookie, or as they were called then, “green” student snipe hunting was another favorite activity. For those unfamiliar with this practical joke, the uninformed victim is taken to an outdoor setting at night with a bag and pillowcase in hand to catch the fictitious creature, the snipe. The group then leaves, swearing to chase the snipe toward the unsuspecting victim and instead returns home, leaving the victim in the dark to discover he has been duped. From this practice comes the old adage “left holding the bag.”

In the Westminster story, the boy was taken out at night by his fellow students from their boarding-house and left with a candle to hold the bag. The others rushed back to the boarding-house and were laughing it up about the prank…that is, until the “green” student crawled out from under the bed in the room in which they were gathered.

Halloween was a popular time of year for pranks at Westminster, but the vogue was not to soap windows, move signs, or destroy anything. The tradition was to do something to the school bell. One time the pranksters simply stole its clapper. Another more imaginative prank was the year the students turned the bell upside down and filled it with water to freeze.

However, the most infamous prank of all was well known by Westminster graduates for years as “the Gun Powder Plot.” In order to provide additional seating in the chapel when it was needed, boards were kept on hand to fasten to the ends of the seats and go over the aisles. When these boards were not being used, they were stored in the chapel. Everything was fine until one day some enterprising students came up with the idea to spread gunpowder along the wall from the entrance to the chapel around to and along the length of the platform and then cover the powder with the boards.

Once the morning scripture lesson had been read and the prayer started, the powder was ignited. The description of what occurred is as follows:

“Following was excitement as genuine as has ever been created. The boards were blown in the air, the chapel was filled with smoke, and the noise of explosion produced pandemonium. Those who were not prepared for the prank thought the house was falling down and made a rush to get out of the building.”

The upshot of the story is every prankster’s dream: No one was ever caught or punished…which was another reason the story became legendary.

Certainly, every generation of Westminster students has produced its share of pranks, but few were ever more creative, elaborate and as explosively effective as “the Gun Powder Plot.”

Dive deeper into Westminster’s history with Westeryears.