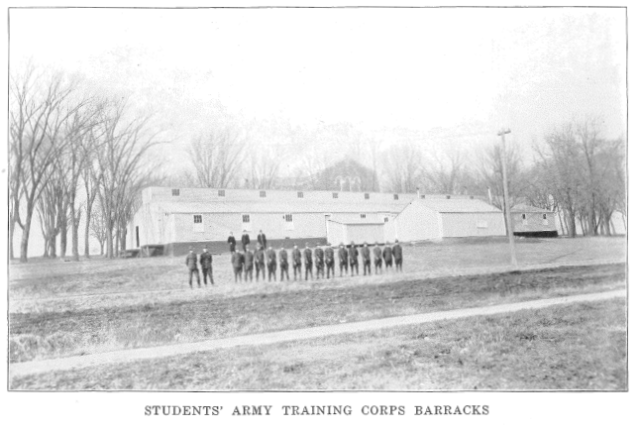

S.A.T.C Barracks at Westminster College

As a part of its mission to serve, Westminster College has built a longstanding and strong relationship with our Armed Services. One brief chapter in the College’s history that demonstrates that connection occurred when the U.S. War Department established a series of Students Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C.) on campuses across America to train officers to fight in World War I.

By making a trip to Washington, D.C., Westminster President Elmer E. Reed was able to secure a contract for a Corps on campus for the fall of 1918. The unit called for 150 men; however, the campus was taken by surprise when 222 were assigned to the unit. Only 67 of them were regular Westminster student volunteers. This situation presented a challenge to the faculty, who had to come up with a plan to incorporate the six required S.A.T.C. courses into the curriculum and find the classroom space and faculty to teach in the program. They were able to develop an accelerated program, which meant the first semester ended before Christmas, and were able to use existing faculty for the instruction.

The Army officially came to Westminster October 1 with Lieutenant Lionel F. Phillips in charge. Lt. Phillips had been pronounced unfit for foreign duty after severely injuring his ankle and foot while training at Camp Lee, Virginia to become a bayonet instructor. He was well liked by the unit as well as his assistant, Lieutenant Henry L. Hasslinger. It is said that, for all practical purposes, these two men ran the College during the brief existence of the S.A.T.C.

To provide housing for the unit, Reunion Hall was used until a long barracks could be constructed north and south along the west side of Westminster Avenue. The early morning sounding of reveille was a daily reminder that the S.A.T.C. had come to campus, or as one member of the unit described the experience, “awakened from sweet slumber by the hated sound of the bugle.”

One of the other dreaded experiences was K.P. (kitchen police) duty where a man might “ladle out hash to a never-ending line of noble men converted into animals by the fierce pangs of hunger,” as one man described it. Or another who said: “What did I do in the Great War? I peeled potatoes in the kitchen for the S.A.T.C.”

S.A.T.C also had its bright spots, such as the weekend pass. One soldier who told the story of his weekend said: “After a long week of Military Law, Special Trig and drill, we would borrow fifteen cents from our corporal, write out a detailed account of where we were going and what we were going to do, get the top sergeant to sign said statement and go forth to pour the sad story of our many woes into Her shell-pink ear.”

Right before the men occupied the barracks, a dance was given there with the entire William Woods student body and young ladies from the town in attendance. The next night the Seminoles, women from Synodical College (earlier the Fulton Female Academy) dined with the men.

One of those responsible for the success of the S.A.T.C. was the President of the Y.M.C.A., J. Paul Jones. When all the men began arriving on campus in late September, Jones found rooms around town for over 200 men until housing could be set up. The local Y held an introductory social event and created a reading and writing room with free stationery offered. When local merchants failed to bid on the rights to furnish a War Canteen for the soldiers, Jones got six of his men released from extra S.A.T.C. duties so they could run a “Y Hut” on the first floor of Westminster Hall. At the “Y Hut” trainees were able to get everything from coffee and mince pie to cigarettes and flowers.

A true hero of this brief chapter in Westminster’s history was Dr. A. J. Courshon. Soon after training began, a flu epidemic hit across the nation. Dr. Courshon immediately started inoculating the entire unit and set up the fraternity houses as hospitals. As a result, not one life at Westminster was lost, while trainees died daily in the units at Missouri University and the Missouri Military Academy. Westminster’s unit was the only one in the state that was never quarantined and the only one that had no cases after the first two weeks. Incredibly, Dr. Courshon took care of all of this with no financial compensation. The men regarded him so highly that when he was ordered to Fort Riley, they gave him a service overcoat, gloves, and a shaving outfit as parting gifts.

Another prominent figure of this time was Mrs. H.H. Turner, known as “Mother Turner,” who ran the mess hall. Her meals were wonderfully home cooked, and she became a mother to all the boys in the unit. She would later become matron of the Phi Delta Theta fraternity house.

In spite of inadequate equipment and adverse conditions, the Westminster S.A.T.C unit achieved the highest record of any school in its division, including several universities. Ten men from the Westminster unit answered the first call to enter officer training camps. Howard J. John, Garrett Grant, Lee Carl Overstreet, George Merry J. Brandom Hope, Kenneth Ashby Head, Theodore Schuster, Ryland Rodes, J.V. Phillips, and V.L. Baker were given a royal send off by the entire unit. Unfortunately, the men only reached St. Louis on the way to Camp Pike, when they were ordered back to Fulton. The armistice had been signed on November 11, 1918. The war was over.

They returned to campus in time for the William Jewell football game, and three of them actually played.

On November 26 word came from Washington, D.C. that the unit should be disbanded no later than December 20. The faculty did vote to hold two short spring terms so that those returning and men who might want to complete a normal year of work could have that opportunity. But the patriotism of the S.A.T.C. unit at Westminster was never forgotten.

This is the editorial account for Westminster College news team. Please feel free to get in touch if you have any questions or comments.

You must be logged in to post a comment.