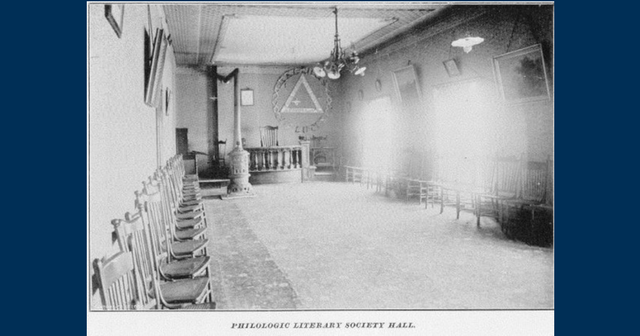

Philologic Hall, 1897

One might think of the conceit of “two households both alike in dignity” from Shakespeare’s romantic tale of the Montagues and the Capulets embroiled in generation after generation of rivalries when discussing the first organizations formed on the Westminster College campus—the Philologian Literary Society and the Philalethian Society. These two groups also hold the distinction of being the first literary societies formed west of the Mississippi.

One of the very first actions taken by the first class of students at WC was to form the Philologian Society January 15, 1852. The organization was formed because the students believed: “to be a man of culture demanded the ability to stand before an audience and express thought clearly and concisely.” Its motto was Dum Spiro Speroi—“While I breathe, I hope”— and the members held secret meetings where they presented papers on topics such as the creation of a great central railroad to the Pacific and the extension of slavery. Most of these papers appeared in a members-only publication called The Casket.

The rival organization, the Philalethian Society, was established November 17, 1854, first as the Polyhymian Society and then changed to Philalethian in February 1855. Its motto was Veteritas Vincet—“Truth Conquers.” This literary society issued a monthly paper called The Argus and had a cover decorated with bright blue ribbons. One 1856 student member, John Cowan, referred to the articles in The Argus as “a little of almost everything…love poems, parodies, dogerel, jokes, riddles, sharp criticisms of students, more or less impudent remarks on the Professors and open comments on peculiarities of citizens of Fulton.” In speaking about one Fultonian rather full in figure, The Argus says: “If flesh is grass, as some folks say, then old man Plunkett’s a load of hay.” To which Mr. Plunkett replied: “that he did not know he was hay until ’till those asses at the college began to nibble at him.”

The second group was the brainchild of Professor of Natural Sciences Samuel S. Law, who thought a friendly competition between students would be good for the College. For the following 60 years, until interest in the two groups waned at the end of World War I, this intense rivalry succeeded above his wildest dreams.

Each group was given a room on the third floor of the newly constructed Westminster Hall—Philologians on the southeast corner and Philalethians on the southwest corner with the library in between. These rooms were kept locked when not exclusively used by the members of the two literary societies, and their meetings were secret with it “high treason for any man to reveal anything that transpired behind their closely guarded doors.”

On occasion, one of the two groups would hold an open evening of passionate oratory, bringing people from miles around to create packed houses for these presentations on topics which might range from “Our Native Land” to “Will It Pay?” Music was performed at the beginning and end of the program as well as between each oration.

One tradition that grew out of the formation of these groups was a joint session early in commencement week for an exhibition of five orations with music in between them on topics such as “Footprints of the Creator” and “The Student’s Hope.” Historical accounts of the 1870 commencement week report two evenings reserved for orations and music from the two literary societies with one of the honorary degree recipients that year, Rev. B.M. Palmer, in attendance, addressing the two groups on Wednesday evening.

One effort to bring the two organizations together was the establishment of the College’s first newspaper, Westminster Monthly, in the 1870’s. Both groups supplied an editor, and the paper, which was circulated to anyone willing to pay the one-dollar subscription fee in advance, published its first issue in April 1871 as a forum for student essays and poems as well as a gossip column and editorials. A March 1877 editorial talks about ball-paying, saying, “We need amusements that will allure us from our cheerless studies” and noting that when playing baseball, “the mind is entirely removed from the dull texts.”

One interesting sidebar occurred when members of Phi Delta Theta from the University of Missouri came to campus to meet with the Philalethians about starting a chapter at Westminster in April 1880. William B.C. Brown, Vice President of the literary society, was initiated that day as the recruiter for the local chapter and by the end of the school year had convinced five other men to join the new group. The men petitioned the national convention and by October, Phi Delta Theta at Westminster had a charter.

When a new chapel was opened adjacent to Westminster Hall’s southeast corner in 1888, the Philalethian Society had the privilege of holding a public event to a capacity crowd as the inaugural event in the building.

Once fraternities came to Westminster and began to flourish, the influence of the literary societies was threatened, for they had already abandoned the exclusivity of secret rituals and now were organizations to promote oratory and declamation. To strengthen the groups’ effectiveness, in 1893, the Board of Trustees began a competition between the two societies during commencement week with a $20 prize going to the winner. Each would hold a separate exhibition, one on Monday evening and the second on Tuesday night, which would be comprised of two declamations, two orations, one essay, and a debate. A panel of judges selected by the two societies would pick the best performance and award the Trustees’ Prize.

Over the years, this tradition collapsed to one day in which the two groups would compete for the Trustees’ Prize on Tuesday night in what was termed the “June Contest.” Earlier in the day, Philologians would hold their own afternoon commencement ceremony to give certificates to society members who were graduating. One attempt by the Trustees to start a third literacy society in 1897 with all students required to join one of the groups was shut down by faculty opposition.

With the Great Fire of 1909, the literary societies lost their halls and the only solution found in the new Westminster Hall that opened in 1912 was to put them in two classrooms on the second floor west in the evenings when the classrooms were not in use. One interesting story of the time from the Parrish book talks about an open session of oration and declamation where the Philathethians invited the Seminole women of nearby Synodical College to attend, but the girls refused to come if they had to walk. After almost an hour of phone calls between the schools and a delay in the program, a solution was found. Taxis were sent for the Seminole girls and “within a few minutes eight pretty Seminoles stepped out of a big Hudson Six and gave nine rahs for the ‘Lethians.'” A huge success, the evening continued until 11 o’clock when the Westminster men sent the Seminoles home in cabs, each with two white carnations and a spray of fern.

Also in 1912, the Dobyns Oratorial Contest, administered by the two literary societies, was started to keep interest high in the literary societies at a time when students seemed less interested in oratory and more interested in debate.

An incident in 1928 almost brought the demise of the societies altogether. The payment for the annual oratorical competition had been two dollars and a half in gold for years. However, when the Gold Panic of 1928 came, the College was forced to pay off in paper money which cost the societies all of its members except for the two sons of “Dog” Lamkin, Henry Clay Lamkin, ’30 and Charles “Pup” Lamkin, Jr., ’29.

After a couple of years of idleness, at the start of the 1931 school year, membership in the two literary societies was made exclusively freshmen, a move to try to keep them active since the majority of the upperclassmen were more concerned with their Greek fraternity life, or as the yearbook described the situation: “all upperclassmen have been converted into incurable lowbrows by English One and Soph Lit.”

By the end of World War II, a society and campus forever changed by war, new interests, and new organizations had no place for the two literary societies, and they ceased to exist. One short-lived attempt was made to revive the Philologic Society in the late 1980’s as a way to “promote intellectual discourse and academic interests outside the classroom.” Although these two distinguished societies from Westminster’s early history may have faded from memory, the leadership skill to “stand before an audience and express thought clearly and precisely” is still taught and considered an essential part of education at Westminster College.

This is the editorial account for Westminster College news team. Please feel free to get in touch if you have any questions or comments.

You must be logged in to post a comment.