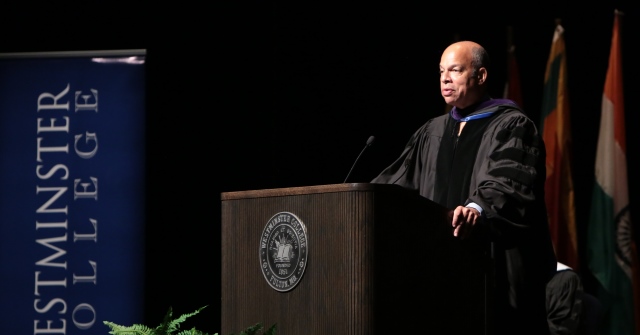

Jeh Johnson is Westminster College’s 56th Green Foundation Lecturer – the full text of his address is below. Explore the history of the Green Foundation Lecture in President Akande’s opening remarks.

56th Green Foundation Lecture

“Achieving our homeland security while preserving our values and our liberty”

Westminster College, Fulton Missouri

by Jeh Charles Johnson, U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security

September 16, 2015

Thank you, President Akande, for that kind introduction. I congratulate you on your new position.

It is an honor to speak at this school. I am impressed that, here in the heartland of America, lies the most diverse small liberal arts college in the Nation, consisting of students from 28 states and 76 countries.

Thank you also for bestowing upon me an honorary degree.

Most of all, it is an honor for me to give the 56th Green Lecture at Westminster College, preceded in this lecture series by an extraordinary collection of presidents, prime ministers, philosophers, rock stars and others who came here to Fulton, Missouri.

Years from now, when learned historians look at the list of Green Lecturers that includes the names Truman, Ford, Bush, Gorbachev, Walesa, and Thatcher, they will say: “who the heck is Jeh Johnson?”

I enjoyed preparing this speech. I am an avid student of history, and there’s a lot of history associated with the Green Lecture series.

I believe the decision-making of public officials should be informed by history. I also believe what has been said many times before — that those who don’t learn the mistakes of history are bound to repeat them.

Of course, the most famous Green Lecture was delivered by Winston Churchill on March 5, 1946 – his “Iron Curtain” speech.1 By March 1946, when Churchill gave that speech, he had been voted out of office as Prime Minister, just a few months after leading the British people to victory in the Second World War.

In 1945 a British newspaper actually suggested that Churchill retire from politics while he was at the top of his game, rather than stand in the forthcoming elections. Churchill responded with a quote that I bet the students here will love. I certainly do. “Mr. Editor, I leave when the pub closes.”2

For Churchill, the pub did close in that election, and he was forced to leave office as Prime Minister.

It was a crushing defeat for Churchill. But, ironically, that loss may have been the reason he found time to come to Fulton, Missouri.

Once here, Churchill had little actual power. He was at that point the leader of the opposition party in the British parliament. But he delivered one of the most powerful speeches of the 20th Century. One that Churchill himself considered his oratorical high-water mark.

Winston Churchill and I have something in common: we were both terrible students in school.

In high school, for me, a C was a gift, and a reason to celebrate. I was a terrible high school student. Students, you are looking at a Green Lecturer who never successfully completed math beyond the 10th grade. In 9th grade I flunked math; in 10th grade I retook 9th grade math; in 11th grade I took 10th grade math; in 12th grade I took 11th grade math, took the New York State regents math exam, and flunked. My guidance counselor suggested to my mother that four-year college was not for me. Somehow, the state of New York let me graduate and go to college, where I was a late bloomer, and improved my GPA enough to get in to law school.

So, as I accept this honorary degree, I feel as Churchill did when he said: “no one has ever passed so few examinations and received so many degrees.”

The man who introduced Winston Churchill to the audience here on March 5, 1946 was President Harry Truman.

Like many others, I am a fan of Harry Truman. He was no intellectual or aristocrat; he was not God-like like his predecessor in the eyes of the people. Not long before Truman became president upon Roosevelt’s death, few people would have deliberately picked him to succeed the great Roosevelt as the leader of the Nation during a time of world war. In the eyes of many, Harry Truman was just a high school-educated haberdasher.

But today Harry Truman is considered one of our great presidents. He rose to the occasion. He had the strength of his convictions, clarity of thought, and a bright compass to lead this country through a dangerous and transformational time.

Five years after Churchill, Harry Truman returned to Westminster to deliver the 14th Green Lecture. And it is that speech by former president Harry Truman, entitled “What hysteria does to us,” that is the inspiration for my remarks here today.

Harry Truman delivered that speech in April 1954. It was during the period of the Red Scare, McCarthyism — the rise and fear of Communism in the post-War, Cold War era. In his usual plain and blunt language, Truman rebuked the specter of McCarthyism with the words, the “descendants of the ancient order of witch-hunters have learned nothing from history.” He went on to say “[t]he cause of freedom both at home and abroad is damaged when a great country yields to hysteria.”3

Dr. Akande, like you, my grandfather was a college president. Dr. Charles S. Johnson was a writer, a sociologist, and president of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, from 1947 to 1956. At the time, Fisk was the preeminent liberal arts college for blacks in this country.

At the same time in April 1954 that Harry Truman delivered his Green Lecture here, about “what hysteria does to us,” Dr. Johnson was defending himself and his school for hiring a professor named Lee Lorch.4

Lee Lorch was a Ph.D., a gifted mathematician, and a white man who could not find continued employment at any white college or university. Lorch was also suspected of being a member of the Communist Party.

In 1950, Fisk was an all-black school that needed a good mathematician of whatever race, so Johnson hired Lorch.

For years Johnson refused to surrender to the Red Scare.

In 1949, he testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee to refute allegations of communist infiltration into black colleges.

In 1948, Johnson, a man with honorary degrees from Harvard and Columbia, was required to testify before a California state senate version of the Un-American Activities Committee — the so-called “Tenney Committee” — about his own membership in the National Sharecroppers Fund, a suspected Communist front. In terms similar to Truman’s, Johnson testified to his view that the Committee’s inquiries amounted to a “witch-hunt,” and “much more un-American than the un-American activities being pursued.”5

Sadly, after years of defending him, in 1955 Johnson had to set aside his principles and terminate Lorch, to protect Fisk University, its standing and its reputation. For Johnson, it was an agonizing decision that, according to one good friend, contributed to his sudden death from a massive heart attack a year later in 1956, at the age of 63.6

Johnson never saw the results of the civil rights movement that he helped harvest. And, it would have been beyond his comprehension that in the year 2013 his own grandson would become the Secretary of Homeland Security.

What Harry Truman said here in 1954 is consistent with views he had been expressing for years. In 1950, Truman asserted in a statement to Congress:

“Everyone in public life has a responsibility to conduct himself so as to reinforce and not undermine our internal security and our basic freedoms. Our press and radio have the same responsibility. . . . We must all act soberly and carefully, in keeping with our great traditions.”7

This assertion is timeless, and I agree with every word.

All of us in public office, those who aspire to public office, and who command a microphone, owe the public calm, responsible dialogue and decision-making; not over-heated, over-simplistic rhetoric and proposals of superficial appeal. In a democracy, the former leads to smart and sustainable policy, the latter can lead to fear, hate, suspicion, prejudice, and government over-reach.

This is particularly true in matters of homeland security.

Today’s Department of Homeland Security is the third largest department of our government, with 22 components, 225,000 people, and total spending authority of about $60 billion a year. Our responsibilities include counterterrorism, border security, port security, aviation security, maritime security, cybersecurity, the administration and enforcement of our immigration laws, the detection of nuclear, chemical and biological threats to our homeland, the protection of our critical infrastructure, the protection of our national leaders, and the response to natural disasters such as floods, tornadoes, hurricanes, and earthquakes.

DHS includes within it: Customs and Border Protection; Immigration and Customs Enforcement; Citizenship and Immigration Services; TSA; FEMA; the Federal Protective Service; the Secret Service; the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center; and the Coast Guard.

DHS is also the agency of the U.S. government with which the American public interacts most.

Given all this, there are a lot of ways in which DHS can potentially assert itself in the daily lives of the American public, in the name of homeland security.

But, as Secretary of this large department with all its resources, I know we must guard against the dangers of over-reaction in the name of homeland security. It’s not simply a matter of imposing on the public as much security as our resources will permit.

Rather, both national security and homeland security involve striking a balance between basic, physical security and the law, the liberties and the values we cherish as Americans.

I understand that the theme of this year’s Hancock Symposium, of which this lecture is part, is “security versus liberty.” National security officials must be the guardians of one as much as the other.

This is why FBI Director Jim Comey requires his agents to visit the Holocaust Museum in Washington, and keeps in his desk the document from 1963 by which the then-FBI Director and the Attorney General authorized government wiretapping of Martin Luther King at his home in Atlanta.

This is why today’s Department of Homeland Security has an Office of Privacy and an Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties that report directly to me, and review all our most sensitive security measures before we enact them.

We must recognize that our first impulse in reaction to a threat to the American people is often not the best one.

This is as true today as it was in Harry Truman’s time.

Today the global terrorist threat to our homeland is evolving. It is no longer limited to terrorist threats that are recruited, trained, equipped, and directed overseas and then exported to the homeland. We now also live in a world that includes the potential home-grown threat — the so-called “lone wolf” — who may strike with little or notice, and is terrorist-inspired by something he sees or reads in social media or the internet.

In this environment, the first impulse may be to suspect all Muslims living among us in this country are potential terrorists.

The reality is the self-proclaimed Islamic state does not represent the Islamic faith, and we must not confuse the two. Spend any time with Muslims in this country and you will quickly learn of their own hatred for groups such as ISIL and al Qaeda. Muslims are the principal victims of ISIL and al Qaeda. To Muslim leaders across this country, ISIL is trying to “hijack” their religion.” Islam is about peace and brotherhood, not violence on others. The standard Muslim greeting “as salamu alaykum” means “peace be upon you.”

Recall also the anxiety a year ago in this country associated with the outbreak of the Ebola virus in west Africa. The outbreak of a lethal virus always raises the potential for public anxiety, because of the great unknown at the initial stages of just how far or fast the virus will ultimately spread. For a period last fall almost every air traveler to the United States, from any part of the world, who got sick on the airplane came to the personal attention of the Secretary of Homeland Security.

In the face of the spreading Ebola virus, I will admit that my first reaction was to limit the issuance of travel visas from west Africa to the United States. The second, better reaction, informed by the views of others on the National Security Council, was that this would be a mistake, because of the United States’ leadership position in the world.

Had we suspended travel from west Africa at the height of the Ebola crisis, other nations would have followed our lead. This would have had the effect of isolating these small African countries from the rest of the world at a time they needed us the most. Instead, we funneled all air travel into the U.S. from Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea to one of five airports here, and thousands of members of the military and the health care profession in this country went to west Africa and helped defeat the spread of the Ebola virus. The United States led, and acted in a manner that should make all Americans proud.

The lesson is this:

I can build you a perfectly safe city, but it will amount to a prison.

I can guarantee you a commercial air flight perfectly free from the risk of terrorist attack, but all the passengers will be forced to wear nothing but hospital-like paper smocks, and not be allowed any luggage, food, or the ability to get up from their seats.

I can do the same thing on buses and subways, but a 20 minute commute to work would turn into a daily, invasive two-hour ordeal. You’d rather quit your job and stay home.

I can guarantee you an email system perfectly free from the risk of cyber attack, but it will be an isolated, walled-off system of about 10 people, with no link to the larger, interconnected world of the Internet.

I can profile people in this country based on their religion, but that would be unlawful and un-American.

We can erect more walls, install more screening devices, and make everybody suspicious of each other, but we should not do so at the cost of who we are as a Nation of people who cherish our privacy, our religions, our freedom to speak, travel and associate, and who celebrate our diversity and immigrant heritage.

In the final analysis, these are the things that constitute our greatest strengths as a Nation.

The last thing I want to say is directed to the students here.

Please consider a career in public service. We need smart, talented and energetic young people to serve their country, their state or their community. I have spent most of my 33-year career since law school as a corporate lawyer. But, I will tell you that my time in public office has been the most satisfying and rewarding, though I make a small fraction of what I earned in private law practice. The one last Churchill quote I will share with you is the one I repeat the most: “We make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give.”

Gratification in life comes from making a difference, and service to others. As college students and young people, many of you have this impulse and this dream. This dream need not die as you grow older. You can really stay until the pub closes.

Thank you.

- Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Sinews of Peace “Iron Curtain Speech,” John Findley Green Lecture (March 5, 1946) (transcript available in the Churchill Museum, https://www.nationalchurchillmuseum.org/sinews-of-peace-iron-curtain-speech.html).

- Anthony Lewis, Churchill is Dead at 90; The World Mourns Him; State Funeral Saturday, NYTIMES, Jan. 24, 1965, available at http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/big/0124.html.

- President Harry S. Truman, Witch-hunting and Hysteria, John Findley Green Lecture (April 12, 1954) (transcript available in the Truman Library, http://www.trumanlibrary.org/hstpaper/soundrecording2.htm).

- See Patrick Gilpin and Marybeth Gasman, Charles S. Johnson: Leadership Beyond the Veil in the Civil Rights Era, pp. 237-248 (2003).

- Id. at pp. 239-240.

- Id. at p. 247.

- President Harry S. Truman, Special Message to the Congress on the Internal Security of the United States (Aug. 8, 1950) (transcript available in the Truman Library, http://trumanlibrary.org/publicpapers/viewpapers.php?pid=836).